Brigit's Forge Website

Pilgrimage to the Hag of Beara

Contact

Blogs

Musings from Gelli Fach

Storing Magic

At the end of 1997 I suffered

an illness which took me off work for several

weeks. Attempting to understand what was

happening to me, I went on an inner journey to

visit my guide, Brigit. As usual I bathed in the

waters of a lake and afterwards went to meet her

under a hawthorn tree a little way from the

lake. She had her back to me as I approached,

and when she turned to greet me, I saw that her

face, instead of being young and lovely as

usual, was old and decaying. I immediately fled

in terror, not waiting to address her or ask her

why she had changed; the image seemed to confirm

my fears that I was approaching death.

I was to find out soon after

this that there is a tradition about the two

faces of Brigit - Lady Gregory writes of one

face that is young and comely and one that is

old and terrible. And there is a Scottish tale

of Brigit or Bride where she is closely

associated with the Cailleach, being her other

face, the goddess who heralds the return of the

Spring as opposed to the Cailleach who holds sway over the

winter; there is a suggestion that they are the

same person. This was a great comfort to me

because it meant that she had not abandoned me

but had appeared in a new guise to show me

something.

With the synchronicity which

often happens during times of change and

development, I happened to meet a friend, Noragh

Jones, in the town one day, and she told me

about her Hag Project and asked me if I was

interested. I knew then what I needed to do -

find and make friends with the Hag, with the

other face of Brigit.

When I recovered I was aware

that the illness had not been about a physical

death but the death of a certain way of being

and an initiation into a new stage of my life. I

was approaching the menopause, my cycle becoming

increasingly erratic. I realised that this was

symbolic of the way in which the pattern and

rhythm of my life was also changing; suddenly

nothing was quite as it had been, the landmarks

had disappeared. I was no longer sure of where I

was or who I was. Inside I felt the same, but

when I looked at the image in the mirror I saw a

much older woman looking back. I felt confused

about who I was and how I should behave.

What I needed to find was my

own way of growing old, to connect with the

inner truth of who I am and how I want to live.

I needed to find the role-models which spoke to

me, inspired me and held out a flame to light me

on my way. I decided to set off on an adventure

which would take me beyond the stereotypes and

caricatures to a place of recognition and

celebration, and so I found myself, one wild and

stormy September night, setting off across the

sea to Ireland.

![]()

Arriving on the Beara Peninsula, I stayed the night at the Garranes Farmhouse Hostel next to the Buddhist Dzogchen Beara Retreat Centre. I got up early the next day before anyone else was awake and went out into the garden to look out over the beautiful ravaged coastline to the ocean. The sky was dramatic, a mixture of huge grey clouds and patches of blue, with the sun streaming through in brilliant rays which always seem to me to speak of the presence of the divine. As I watched a ship sailed slowly out of the greyness into the brilliant pool of sunlight and then slowly out again into the greyness on the other side. It reminded me rather appropriately of the Venerable Bede’s sparrow flying through one window into a lighted hall, symbolic of life, and then out of the opposite window into the dark again.

After breakfast I set off for Dursey Island, once called Oileán Buí. Buí is one of the names of the Cailleach Bhéarra, the Hag of Beara, and it is said that she formed this island at the tip of the Beara Peninsula. The Old Woman of Beara is an important figure in Celtic folklore. Her age is proverbially great - ‘the age of the yew, the age of the eagle and the age of the Cailleach Bhéarra’ - and a footnote to the poem ‘The Lament of the Old Woman of Beara’ says that “she passed into seven periods of youth so that every husband used to pass to death from her, of old age, so that her grandchildren and great-grandchildren were peoples and races.” This is one of the mysteries of the Cailleach that she contains within herself both youth and age; she is both crone and maiden, renewing herself seven times to give birth to a people and so becoming the divine ancestress. Who then more suitable to visit and honour in my own quest for the wisdom of ageing?

I took with me Noragh Jones’ Meditations for Hag Sacred Sites on the Beara Peninsula. I had hoped to start with the meditation on wilderness on Dursey Island, but the morning, by the time I reached the crossing-place, was cold and stormy. The crossing by cable car above the harsh waters of the Atlantic looked precarious and the island itself lacked shelter. I made the decision not to go but to find a place in the hills overlooking the sea to do my meditation. To find a place where there were no people or houses, I ended up driving a little way and eventually coming across a rocky hill I climbed it and then sat, gazing out over the water as it crashed with white spray onto the numerous rocks and small islands around the bay. By this time the sun had come out and in its light the water was a deep blue, the rocks brown and grey, the grass green - as only Ireland can be green. In the far-off I could see the other peninsulas. I began to feel that this place was not wild enough, that I should have gone somewhere wilder, bleaker, more remote. I felt I wasn’t testing myself enough, I should have braved the elements and gone over to Dursey. I started to imagine being in one of the bleakest and wildest place I have ever seen - the sea at the foot of the Cliffs of Mohar on the Burren, a place absolutely inhospitable for humans. I was making quite a good job of imagining I was there, my inner vision enhanced by the sound of the sea crashing on the rocks around me, when I suddenly stopped short. I looked around me, nothing to see but sea and rock and sky, no human presence or habitation. “Where I am is wild enough”, I thought. “Why do I always have to push myself to extremes, to try and imagine the very worst place I could be?” I realised that this is what I do. And I realised how much energy it takes. In the past this has had a positive role to play - I have looked for challenges and adventures and pushed myself to find out what I am capable of; my life has been enriched by this. But the negative side is that it has used valuable resources and I have gone where other people have no wish to go and in some ways become isolated. “Now is the time”, I thought, “to come in from the cold, outer reaches of the world, and like a traveller coming home full of riches and experiences, I can use them to enhance the place I have come home to.”

I continued to sit and

Noragh’s words began to echo in my mind -

“Walking the wilderness in the second half of

life means going beyond the roles we use to give

us outer identity. It means finding out who we

are when we stop measuring ourselves by the

standards of youth.”

I thought of the Cailleach as the Shaper of the Land. In Scottish tradition the Cailleach Bheurr is thought to have carried rocks from Norway to form the coasts and mountains of Scotland. As she flew over Meath in Ireland she dropped cairns on the hills and many of the rocks and islands around the south-west coast were created by her. I thought of her striding over the landscape, dropping stones where she pleased, forming lakes from her piss, and I was caught up in the power of that image, the autonomy, the sovereignty of it; that she did not ask permission or feel ashamed of what she did. I saw her as a woman above and beyond all restriction that society might want to put on her, a woman in fact, who in some ways shaped society herself by determining the landscape in which it existed... This idea had a powerful effect on my inner musings about who I was, how I fitted into society and what was correct behaviour for a woman of my age - by determining what was right for me and doing it, I could have a role in shaping the world around me, rather than being shaped by it.

On my way down the hillside, I stopped for a pee. It disappeared almost at once into the ground - no puddle, let alone a lake! Undaunted I carried on, back down to the road and set off on the next stage of my journey.

![]()

Finding the Hag

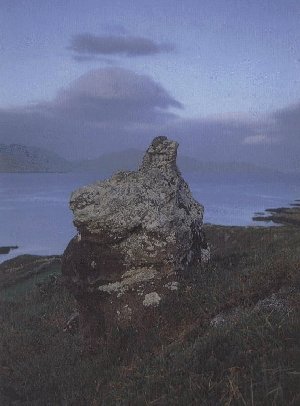

Eventually I stopped for lunch in the village of Allihies where I sat in the sun and shared my cheese with a scrawny cat. At last I came to a sign ‘An Chailleach Bhéarra’ pointing to a path beside the road. An Chailleach Bhéarra is an ancient, strangely shaped stone made of metamorphic rock which is completely unrelated to any other rock in the area. Local people say that the Cailleach turned herself to stone so that there would always be a Hag on Beara. Standing on the hillside above Coulagh Bay, she gazes out over the Atlantic Ocean.

It was only a short walk to reach her, but the ground was so boggy and wet that I had to go back to the car for my wellington boots. Reaching her at last I was amazed to see that she was covered in coins - every surface and crevice was shining with ‘copper’ and ‘silver’. They seemed to me to symbolise her value and I was pleased that I was not the only one to make the journey to visit her.

I sat on the ground beside her and in companionable silence we both looked out over the bay. The day was by now hot and sunny and a feeling of peace hung lazily over the air like a swarm of good-natured bees.

I began to meditate more about ‘shape’. The stone beside me was huge and ‘misshapen’ in the sense that it was totally irregular, bulging here and there with what looked rather like a head on one side and a smaller excrescence on the other. But really it defied description. I thought of the Cailleach not only shaping but also being her own shape. The hag is very often described as a hideous misshapen old woman, indeed one of the Welsh words for hag, gwiddon, also means giantess or monster. But sitting there beside her I had a sense of her beauty and power, a beauty which transcended the aesthetic values our society confers on certain shapes. I felt that her outward form was irrelevant to her; that she was sure enough of herself, of her essence or spirit, to simply be. She is an embodiment of the land, not bound by human perception, although being a creator she is able to change her own shape as well as that of the land. Like the very stone beside me which was metamorphic rock, already changed from its original nature, she could appear in other guises. She was said to appear to young men such as Niall and Lugaid first as a loathsome hag and then, when they agreed to sleep with her, as a beautiful young woman. In this the Hag acts as the Goddess of Sovereignty, conferring kingship upon those she finds worthy - those who understand and do not recoil from the darker and uglier side of kingship, perhaps also those who are able to see beyond outward form or shape to her inner beauty which is the essence of the land, of the earth itself. This is, for me, one of the mysteries at the heart of the Hag; the seeing with inner vision the beauty of the creation in all its forms, for the Hag has lived as long as the oldest rock on earth and contains in herself all ages, from maiden to mother to crone.

It is said locally that one can see in the rock not only the hag but also the young woman and I walked around her, viewing her from all directions, without, however, seeing either one clearly. There was some suggestion of a huge, lumpy, big-breasted woman, but the way she chose to reveal herself to me on that day was as a cow - a cow after all, is a large female animal with huge udders. The Cailleach Buí is associated with cows on the Peninsula for there is a stone called Bó Buí, Buí’s Cow, which stands in the sea next to Inis Buí by Dursey and which is said to have been turned to stone by the her. And scholars have noted that the early names for the Cailleach, Sentainne Bérri and Boí/Buí, come from the Indo-European root Senona and Bovina meaning respectively ‘female elder’ and ‘cow-like one’.

I had noticed with wonder how many cows there were on the Peninsula. Where I come from in Wales the comparable rocky and hilly terrain is covered in sheep and cows are rarely seen. Earlier I had witnessed a scene where a farmer was leading his cows across a field. The gate of the field where they had come from had swung shut trapping a calf, and the mother cow was distressed and would not go on without it. Later, on my way to visit the tallest ogham stone in Ireland, a huge cow had loomed suddenly out in front of me, blocking my path, and below me now, on the hillside, were three cows grouped in a tableau in a small field that appeared to jut out over the bay. They seemed to be looking out over the water and hardly moved throughout my stay. So I had been aware of the presence and energy of cows already, and now ‘seeing’ the Cailleach Bhéarra stone as a cow, I started to meditate upon them.

In

popular slang, ‘cow’ is a derogatory term for a

woman, often prefixed with ‘fat’. So it has

associations not dissimilar to ‘hag’ - both

denote a supposedly unattractive woman, often fat or

monstrous in shape. Yet to the early Celts, to

call a woman a cow was an expression of

approbation. In an Irish poem ‘The Siege of

the Ridge of the Stag’s Cry’, the poet talks of:

Eimhne gentle many-beautied

in my joy much magnified,

gentle handsome flower-bright

my woman, she the cow,

let her have no reason

to lament.

trans. Seán Ó

Tuathail

and the Carmina Gadelic from

Scotland contains a milking croon which calls:

Come, beloved Colum of the fold,

Come, great Bride of the flocks,

Come, fair Mary of the cloud,

And propitiate to me the cow of my love.

Ho my heifer, ho heifer of my love”

showing how much the cow was an object of affection. It was a symbol of wealth and status, and more than that, it provided nourishment which ensured the survival of the tribe. One of the Triads of Ireland says: "Three slender things that best support the world: the slender stream of milk from the cow’s dug into the pail, the slender blade of green corn upon the ground, the slender thread over the hand of a skilled woman.” So I was aware of the shape of the Cailleach as both the lovely heifer, and the fat cow, sustaining the world. And of the millions of women, fat and thin, who have nourished and sustained their children and their men, their families and their communities, since time began.

I was also very much aware, sitting there, of the sexual energy of the Cailleach which, like the feeling of peace, hung tangibly on the air. Unlike the more beautiful, rather virginal images of Mary and Brigit, sexuality is very much a part of the Cailleach’s story and lore. I remembered some lines from Brendan Kennelly’s version of the poem ‘The Lament of the Old Woman of Beara’, an early Christian poem which depicts the Cailleach taking the veil in later life and lamenting her younger days. Some say that in the poem she is also lamenting her pagan past when there was no restriction on her taking young lovers, unlike the Christian present when she had to be chaste and live a regulated life in a nunnery.

The young sun

Gives its youth to everyone,

Touching everything with gold.

In me, the cold.

The cold. Yet still a seed

Burns there.

Women love only money now.

But when

I loved, I loved

Young men.

Young men whose horses galloped

On many an open plain

Beating lightning from the ground.

I loved such men.

I had always liked these lines, the relish, the celebration in them. Now I thought back over my own youth and the young men I had loved. I had enjoyed my sexuality then, had felt the golden touch of the young sun and delighted in its warmth. As I sat beside the Cailleach I remembered this period of my youth, and reclaimed it, and rejoiced.

The feeling of rejoicing also

came through to the present. As a single ageing

woman I had sometimes wondered about my sexual

role. Older women are not generally portrayed as

sexual beings, except in a ridiculous or comic

way, and in May when young men and women

traditionally came together in ceremony and

union, I often felt out of step, as though I

should have left behind this activity of meeting

and mating as I moved into motherhood and

beyond, to another archetype, that of the wise

old matriarch, ostensibly asexual.

But I knew that this was not the reality. As the poem says “Yet still a seed burns there”. The desire for physical intimacy and sensual pleasure does not necessarily diminish with age, though some may be happy to let it go. Indeed, often after ‘the change’ women are able to enjoy sex more, freed from the fear of pregnancy. The Cailleach knew this too, and I felt a conspiratorial companionship with her as we both stared out over the deep, abundant waters of the ocean. Again, I was reminded of her mystery, that she contains all ages and all seasons within her, both winter and spring, and that, like her, our inner cycles move and turn, and we are renewed.

The Cailleach is also present in the image of the slender green corn, for she was known too as a corn goddess who knew the secret of producing early and abundant corn, and she protected the harvest. Returning to Noragh’s Meditations I began to think about my own harvest, of what I am reaping at this autumn time of my life.

Looking back at my life, I was able to see it spread out behind me like a piece of woven cloth, or like the pattern of fields, stone walls, houses and roads that filled the landscape below me. I was reminded of a traditional Welsh song which says:

I weave my fragile life in the loom, in the loom

And a hidden pattern I create in the loom, in the loom

I put the greying thread of pain

White thread of joy

And love, its wondrous scarlet, in the loom, in the loom

To sleep as one in the end,

in the loom, in the loom.

trans. Meredith Robbins

I could see the different

places I had lived and been, the people who were

important in my life, the things I had done. I

could see the threads of pain and joy and love

and, from this distance I could evaluate what

had been good, or where I had made mistakes or

wrong turnings. Some of the colours and the

patterns were beautiful and I delighted in

looking at them; some of them were dark or

ill-formed, yet, being so, they highlighted the

beauty of the others and gave more depth and

interest. Seeing brings knowledge, insight

brings wisdom, so that being able to look back

and see one’s life in this way confers knowledge

or wisdom upon us, and gives us the vision to

live well in the future, and advise others - one

of the traditional roles of the old woman.

Having lived long enough to observe patterns, to see actions and reactions, cycles of birth and death on many levels, we cannot help but have more knowledge of the nature of things. And knowing this, it is easier to predict the way of things and therefore to be more calm and serene about outcomes. We may lose the energy and idealism of youth, but with age we can sometimes conserve energy by knowing what actions will be wasted and what will not. Again, idealism very often fails to take account of the darker side of human nature which is with us all and must be respectfully acknowledged. It takes time and experience to understand this.

So that was my harvest - the beginnings, hopefully, of wisdom and a greater serenity which comes from understanding more, and from finding my place in the world.

![]()

Keeping the Flame of Life Burning

With this in mind, I moved on to the last phase of my pilgrimage, a visit to the ancient church of Kilcatherine, just a little way along the road. There is a story that the Hag stole a Mass Book from the priest of Kilcatherine while he was asleep. When he woke up and discovered the Book was missing, he pursued the Hag and turned her to stone on the edge of the cliff.

I read in Noragh’s notes that the church had been built on the site of an early Celtic Christian nunnery. St Catherine, like St Brigit, was a great organiser who had set up a chain of women’s monastic houses in the West of Ireland. Holy women like these had carried the flame of women’s spirituality when the pagan deities had been displaced. The monastic houses were centres of support for the poor and sick and needy and therefore, in a mundane way, had taken over the Cailleach’s role as provider of the harvest and mother to her people.

The church was now ruined and grass and flowers grew inside it, while the windows were open to the elements, the corbelled arches reminding me of New Grange, and the beehive huts of Kerry. Strikingly framed through the west window was the sea, while through that of the south were hills and sky. Again I had a sense of vision. I looked through the window to my life now, and meditated, as Noragh had suggested, on my public persona; on how I keep the flame of life burning in my everyday activities and whether I work in my community to help the people prosper. Almost immediately a wave of guilt swept over me - my illness the previous year had convinced me to start working part-time and to spend more time doing things for myself, either socialising or creatively. But there was a part of me that could not but help see this as self-indulgent, particularly when I was enjoying myself. Even when I was working full-time I felt as if I could have done more. If I looked at St Brigit as a model, then I should be always ready to help others and to give away everything I had. For a while the brightness and magic of the afternoon faded, as I contemplated, not for the first time, my inadequacies. But then, in reaction to this, my perception of earlier that day near Dursey came back to me - how I always push myself to extremes. In this case I was measuring myself against a Christian saint!

Another gift of age is self-knowledge and self-acceptance, and I moved perhaps a little nearer to this as I realised that, being no saint, I have to work within my boundaries and the limitations of my energy. ‘To be a source of strength for others, one has to nurture one’s own strength’ someone had told me. And I knew from my work with Brigit that creativity and joy are sources of energy and renewal - both essential if one is working as a healer. Since life is flow and change, the only way to live healthily is to participate in this flow; as we give, we need to receive and vice versa - in this is sufficiency and replenishment.

I realised again that it was time for me to stop expecting to live on the extreme edges of life; time to use my experiences to enrich a gentler way of living, time to take out and examine all that I have felt and discovered and learnt in my life so far, and to use it creatively in ways I have not had the time to explore before. Time to accept myself with all my limitations and failures, to find, as it were, my own shape, and in doing so, find my wholeness.

By this time the sun was beginning to sink down in the West, and gathering myself together I left the gentle silence of the ruined church, and returned to the car. Driving back to the hostel I was left with an image of the stone that is the Hag of Beara. Whether she had turned herself to stone or whether a Christian priest had done so thinking to punish her, she still radiates her essence into the world and brings people to her to receive her wisdom. She knows well how to use her energy, and even confined to one place her spirit travels - as strong and powerful as the elements themselves.

© Hilaire Wood 1998