Brigit's Forge Website

Brigit in Wales: Sant Ffraid

Contact

Blogs

Musings from Gelli Fach

Storing Magic

In Wales Brigit is known

as Sant Ffraid, Sant Ffraed or Sant Ffred.

In Welsh an 'f' is

pronounced like 'v' in English and 'ff' denotes

the English 'f' sound.

This change of the initial letter came about

because the name Brigit was

borrowed into Welsh as part of a compound word,

in English 'Saintbrigit', Old Welsh

san(t)bregit, the form in which it appears

in the Book of Llandaff. It is a rule of Welsh

that the second element in a compound word

undergoes a kind of regular softening called

'lenition': normally a b- turns into a v-, but

in this instance the effect of the -t of 'sant',

(Welsh for 'saint, holy') causes the resultant

v- to 'harden' into an f- sound. So if you try

to say 'santvraid'

it naturally becomes

'santfraid', because of the -t

before the

Brigit’s name often appears as Sant Ffraid

Leian, St. Ffraid, the Nun. She was highly renowned in medieval Wales – only the Virgin

Mary, the Archangel Michael and David, the

patron saint of Wales being more popular. Her

cult was founded in those parts of the country

that were colonised by the Irish up to the 7th

and 8th centuries and became widespread.

renowned in medieval Wales – only the Virgin

Mary, the Archangel Michael and David, the

patron saint of Wales being more popular. Her

cult was founded in those parts of the country

that were colonised by the Irish up to the 7th

and 8th centuries and became widespread.

Iorweth Fynglwyd

(c. 1480-1527),

a Welsh poet of St Bride’s Major in Glamorgan, wrote a poem in honour of St Ffraid in which he gives an account of her

legendary life and describes the various

miracles performed. He refers to her as

'morwyn wen',

'white' or

'blessed' maid and as 'morwyn ddedwydd',

'blessed or 'happy'.

[1]

This the only existing

source for the legend of Brigit in Wales and

records that:

She was a beautiful Irish nun, the daughter of Dipdacws (Dubtach) of ducal lineage; she procured honey from a stone for the poor; she gave a distaff to a ploughman to do duty for his broken mould-board; she converted butter that had been turned to ashes to butter again; she gave a certain cantref all the cheese in the steward’s store, but not so much as was ever missed by him. She knew the Fifteen prayers; whenever it rained heavily she would throw her white winnowing sheet on the sunbeams; when her father desired her to marry some one she did not like, one of her eyes fell out of its socket which she afterwards put back and it was well after; she sailed on a piece of turf from Ireland and landed in the Dovey; she made out of rushes in Gwynedd, the beautiful fish – without a single bone – called brwyniaid (smelts) which she threw out of her hand among the water-cress; she went to Rome to St Peter’s; Jesus established her festival on Candlemas Eve and it was observed with as much solemnity as Sunday. [2]

Apparently there was once a

longer metrical version of the legend which says

that she floated over with her companions on

pieces of turf and landed at Porth y Capel, near

Holyhead. She built a chapel on the bank there

and went on to Glan Conwy where she founded

Llansantffraid and turned rushes into the small

fish called smelts or sparlings (Welsh

brwyniaid) which she threw into the

river Conwy.

[3]

Smelts or sparlings were called pysgod Sant Ffraid in that area and at least until the beginning of the 20th century the legend was still alive in the Vale of Conway. [4] There was a tale, collected by the Welsh Folk Museum from a woman at Conwy, the only area where the fish are found, that when St Ffraid lived there, there was a terrible famine and St Ffraid saved the people by turning the rushes into sparlings. According to this story, St Ffraid was walking by the river and without thinking threw rushes into the sea. A few days later ‘he’ - the informant thought that St Ffraid was male - saw what seemed like stars shining in the water and discovered they were fish. ‘He’ then knelt and prayed to thank God for them. The fish are supposed to taste of rushes and the Conway is known for them. This mistaken identity makes it more likely, according to Henken, that the story came from an inherited tradition rather than being based on a written account and shows the importance of the tale in the community, independant of any other traditions about the saint. [5] The story related by Iorwerth Fynglwyd, however, says that St Ffraid created the sparlings out of the rushes for the feast at Easter, not for a famine. She did so intentionally whereas in the folk tradition they were created unintentionally, simply as a result of her holiness.

Another connection with fish is attested in Pembrokeshire where fisherman were known to pray at the Chapel of St Bride before they went fishing. Eventually the chapel fell into ruin and when it was made into a salt house the fishing failed, as recorded in the rhyme:

When St. Bride’s chapel a salt house was made,

St. Bride’s lost the herring trade. [6]

As we have seen, there are two traditions about where Brigit made landfall in Wales: in one she arrives in the Dyfi (Dovey) estuary, possibly, according to Gossiping Guide to Wales, at a place near Talybont called Ynys y Capel [7]. The other tradition, as already mentioned, is that she arrived near Holyhead and built Capel Sant Ffraid which stood on a mound on a sandy beach called Tywyn y Capel, now Trearddur Bay, about two miles from Holyhead. There is none of it left now but a stone cross, the Millenium Celtic Cross, was erected to mark the year 2000, above the beach at Trearddur. The words "St. Bride, Pray for Us" are inscribed in four languages, English, Latin, Irish and Welsh, one on each side of the plinth, and halfway up the 8 ft cross is a carving of a hand carrying a flame which symbolises the flame of Kildare. At the head of the cross is carved ‘Cross of Peace’ and superimposed on the arms of the Celtic cross is the cross of St Brigit of Kildare. The cross is situated just behind the promenade on Towyn y Capel beach, the old name for Trearddur Bay

. [8] .

A river on Anglesey, the river Braint is named

for Brigit. It is located on the opposite side

of the island to Holyhead, between

Llannerchymedd and Llyn Alaw. It rises as a

stream on Mynydd Llwydaith and flows parallel

with the Menai Straits (the stretch of water

that separates the island from the mainland)

until, in its lower reaches, it enters the strait

below Dwyran.

In the early Welsh poem Gofara Braint,

the river Braint overflows as a result of the

death of king Cadwallon. This suggests a

connection with the

ancient concept of the marriage of the

sovereignty goddess to the ruler of the land.

D.A. Binchy argued that the Welsh word for king,

brenin, had originally specified the king

as consort of the tribal goddess Brigant.

[9]

Stepping

stones on the River Braint

photo:

www.hedgedruid.com

It is interesting to note that the Dyfi and the

Conwy are the two rivers also connected with the

poet Taliesin, both said, in different versions

of his tale, to be where he arrived after

Ceridwen put him in a leather bag and cast him

into the sea.

Elis Gruffydd, in his mid 16th

century version, which is the earliest we have,

says it is the Conwy;

other versions say it is

the Dyfi. Lady Guest’s version of the tale in

her Mabinogion translation gives the Dyfi but

she used as one of her sources a text in the

hand of Iolo Morganwg who was known as a forger

of antiquities, so it is possibly less reliable.

Still, it is interesting to find both rivers

connected with places where two inspirational

figures made landfall. The Conwy derives from

the Welsh Cynwy: ‘cyn’ meaning ‘chief’

and ‘wy’ meaning ‘river’. There is

evidence of occupation along the Conwy valley

going back to the Stone Age and the Romans built

the town of Conovium on its banks. The Dyfi

shares its watershed with the rivers Severn and

the Dee and old lead and slate mines are found

in the surrounding area. Both rivers are renowned for salmon

and trout.

The legend used by Iorwerth Fynglwyd seems to be a composite of several different Saint Brigits, including Brigid of Kildare, Brigid of Cill-Muine, and St Bridget of Sweden, as well as descriptions of some local Welsh traditions. The ‘fifteen prayers’ alluded to must be the fifteen prayers which were taught to St Bridget of Sweden in a vision. They were translated into Latin and widely distributed by English members of the Brigittine Order in the 15th Century, when Iorweth Fynglwyd was writing. [10]

Baring-Gould and

Fisher assert that "there can be no question

that the Brigid who was in Wales was an entirely

distinct personage from the Brigid of

Kildare..." They assume that the fame of the

saint of Kildare subsumed the other holy Brigits

so that the name became identified with her

exclusively. There is no record in the Irish

Lives of Brigit of Kildare travelling outside

Ireland (although there is a persistent legend

that she lived for a time in Glastonbury and

there are churches dedicated to her in other

parts of England, as well as Scotland.) Brigit or Brig

was a popular name and St Brigit had several

disciples of the same name as herself; there were

apparently ten St Brigits and fourteen St Brigs.

Baring-Gould and Fisher tell us that in the Tallagh Martyrology there are as many as seven Brigit commemorations apart from Brigit of Kildare; and in the Martyrology of Donegal is a Brigid of Cill-Muine or Menevia (present day St David’s in Wales)commemorated as a distinct personage on November 12th. In the Martyrology of Gorman she is described as “the gracious Brig with a (conventual) rule”, and the gloss adds, “Brig and Duthracht, from Cill-Muine were they.” So this Brig is definitely a separate person to Brigit of Kildare.

The Life of St

Monynna or Darerca relates that the abbess Monynna sent

Brig to Cill-Muine to learn the rules of

monastic life. Later on Brig saw two swans

flying away from the cell where the abbess was at prayer. When she told Monynna this, the

abbess sent her away to found a religious house

of her own and decreed that she should be blind.

It seems likely that this Brigit is the Brigit

who became known in South Wales.

Baring-Gould and Fisher also tell us that in the life of another female saint, Modwenna, by Concubran, we learn that Modwenna together with three others – Brigid, Luge and Athea - came over the sea from Ireland on a piece of detached ground, and landed by Deganwy Castle, near Conway. Brigid and Luge were left there by the other two who continued on to Polesworth and the Forest of Arden. They conclude that:

But we may safely assert that two Brigids visited Wales, one was in Mynyw, [St

David’s] another in Gwynedd, and both were

distinct from Brigid in Kildare.

Some of the traditions related by Iorwerth Fynglwyd conform to those of Brigit of Kildare, for instance, she is Irish, the daughter of the chieftain, Dipdacus, (Dubthach); she plucks her eye out rather than marry; she performs a miracle of plenty with ale. However some of the stories do not.

Brigit of

Kildare is associated with the milch cow – she

was nurtured by the milk of a white cow with red

ears as her foster-father’s food was not pure

enough for her, and performs several miracles

connected with milk and milk products, thus

showing her purity, her nurturing aspect and

mastery of the vital skills of dairying. The two stories concerning dairy products

mentioned in the Welsh poem do not appear in the

Lives of Brigit of Kildare: in one she turns

ashes into butter, in the other she takes the

cheese from a miserly steward’s house and makes

it grow to feed the whole cantref. Other

legends not included in the Vitae from Ireland

show the Welsh St Ffraid using a distaff as a

plough mould-board (the curved plate of a plough

that turns over the soil), drawing honey from a

rock and causing her step-mother’s leg to

re-grow after it has been cut off. There are

also curious references to stories now lost of

her turning the Mayor of London into a horse and

freeing the baker’s wife before the Pope.

Iorwerth’s

cywydd mentions Brigit making beer:

A chwrw a wnaud, chwaer i Non/ mewn deugawg, mwy no digon.

And you would make beer, sister to Non, in two

pitchers, more than enough.

St Brigit of Kildare was famous in Ireland for

her connection with ale. She was said to have

transformed water in ale and once when lepers

and poor people begged her for some she told

them all she had was her bath-water – which was

then transformed into excellent beer. She also

managed to supply seventeen churches in Meath

with ale from Maundy Thursday to Low Sunday, even

though there was a scarcity of malt and corn.

An 11th century Irish poem

attributed to St Brigit taken from a manuscript

in the Burgundian Library, Brussels and edited

and translated by O’Curry contains the stanzas:

I should like a great lake of ale

For the King of Kings;

I should like the family of Heaven

To be drinking it through time eternal.

I should like the men of Heaven

In my own house;

I should like kieves [an Irish word for a basin

used for mashing the grain in beer-making]

Of peace to be at their disposal.

I should like vessels

Of charity for distribution;

I should like caves

Of mercy for their company.

I should like cheerfulness

To be in their drinking;

I should like Jesus

Too, to be here (among them).

I should like the three

Marys of illustrious renown;

I should like the people

Of Heaven there from all parts. [12]

As

well as associating Brigit with Peace, Charity

and Mercy, she also appears here as a

woman who likes a feast with plenty of

ale and divine company. But there may be

overtones of a more pagan feast, for the

Irish smith Goibnu of the Tuatha Dé Danann, one

of the three gods of skill, was said to provide

great quantities of ale which conferred

immortality at a feast of the gods, Fled

Goibnenn. Certainly there are echoes here of

the Celtic style of feasting.

As

well as associating Brigit with Peace, Charity

and Mercy, she also appears here as a

woman who likes a feast with plenty of

ale and divine company. But there may be

overtones of a more pagan feast, for the

Irish smith Goibnu of the Tuatha Dé Danann, one

of the three gods of skill, was said to provide

great quantities of ale which conferred

immortality at a feast of the gods, Fled

Goibnenn. Certainly there are echoes here of

the Celtic style of feasting.

We may also note that many ancient Irish texts connect poets with the word meisce which can mean ‘in a mental ferment’ as well as ‘intoxicated’, and often describe them as being heated or having inflamed faces while composing. In another context, ale is connected with the giving of kingship and more than one scholar has suggested that Brigit is a Christian version of Queen Medb of Connacht, whose name means ‘she who intoxicates’. [13]

In Wales, St Brigit is associated strongly

with ale. The custom known as “Cwrw Sant

Ffraid”or St Bride’s Ale, is mentioned quite

often, for instance, in the 13th to

14th century Red Book of Asaph, “quaedam

consuetude vocato Corw Sanfrait”.

It is also mentioned in the poems of

Dafydd ap Gwilym and Iolo Goch, among others. A

rhyming calendar in Cardiff Library, MS. 13,

written in 1609 mentions her festival:

Digwyl San Ffraid ydoedd fenaid,

I bydd parod pawb ai wyrod

St Brigit’s Day it

was, my soul,

Everyone will be

ready with his drink.

And another

popular poem celebrates the

Ffridiau gwin San

Ffraid Gwynedd

Streams of

wine of St Brigit of Gwynedd

[14]

The records of the lordship of Dyffryn Clwyd (modern Denbighshire) mention the custom of cwrw gŵyl Sanffraid, beer of St Brigit’s Day. It appears that the Welsh people of Dyffryn Clwyd had been celebrating St Brigit’s Day by drinking a significant amount of ale, which, before the English conquest, was supposed to be provided by the locals to their local Welsh lord, who would then distribute it fairly. Specific amounts of beer to be provided by the individual members of the community for the feast were allotted to the inhabitants. The English, however, turned the beer allotment into a money fee of 5 shillings, which was quite a large sum for the time, and this essentially killed the custom by the end of the middle ages. [15]

St Bride on right hand of king of heaven,

Llansantffraid ym Mechain

St Ffraid and Pilgrimage

An anonymous poem called Kyntaw Geir in the 12th c Black Book of Carmarthen

describes someone about to set out on a pilgrimage to Rome asking Christ, Saint Peter

and St Brigit to protect him on his journey:

O eissillit gudelic.

A gueith wtic. Wosprid

a phedir pen pop ieith

Sanffreid suyna de in imdeith.

Offspring of the ruler, victorious Redeemer, and Peter head of every nation,

St Brigit, bless my journey. [16]

By the ninth century Brigit had a reputation connecting her with pilgrimage and there are accounts of her views about it in several sources. [17] Iorweth Fynglwyd’s cywydd tells us that St Brigit went to Rome to St Peter’s, although in fact the Irish accounts reveal that she sent seven men to Rome to learn the rule of Peter and Paul since she herself was not permitted by God to go. Women did not have the ease of movement that men had in the early medieval period. However this did not stop Brigit being called upon by travellers to Rome – St Cadroe of Metz, a 10th century Scottish monk and pilgrim went to the "house of the blessed Brigit", presumed to be the monastery dedicated to Saint Brigit at Abernethy, to pray before leaving Scotland - and the pattern of churches dedicated to Brigit of Kildare in Italy suggests they may have been founded to aid pilgrims. Donatus Scottus, an Irishman who became the bishop of Fiesole, owned a church in Piacenza which was dedicated to St Brigit. He gave it to the monastery of Bobbio with the condition that if any Irish pilgrims came there they were to be taken care of. Brigit may have been the saint most often invoked by Irish pilgrims which would explain why she is the most well-known of the Irish saints in Europe. [18]

Lewys Glyn Cothi,

in the 15th century, swears by her

shrine: ‘Myn bedd Sain Ffraid!’ in an

elegy for Rhys Ab Davydd Ab Hywel Vain:

Rhan darvu o’i

lu roi’n welyaid

Cyweiriawdr i

bawb o’r cywiriaid;

Cerddoriaeth sy’n waeth myn Croes naid!

Canu a phrydu myn bedd Sain Fraid

! [19]

Here the poet seems to be lamenting the fall of the order of things with the death of Rhys, implying that there is no hope for music, singing and composing verse. The mention of St Ffraid alongside a reference to music and poetry is no doubt a happy accident almost certainly for the purpose of the rhyme scheme.

The betony, betonica officinalis, is called in Welsh ‘cribau Sant Ffraid’, the ‘combs of Bride’. According to the 12th century Welsh physicians of Myddfai, betony was good for many things, including colic, strangury and coughs, but especially for the eyes, if boiled with leek seed or mixed with the juice of red fennel and clear honey “curing them if diseased and strengthening the five senses wonderfully”. They also comment: "And a wise man has said that if reduced to powder, a snake would rather be broken to pieces than pass through the powder". [20]

In the present time Betony is found to be a sedative and to have a strengthening effect upon the nervous system. It is useful for headaches and neuralgia caused by stress and tension.

Several people were named Gwas Sant Ffraid in the

Middle Ages. It

means the (tonsured) servant of St Ffraid and is

the equivalent of the ‘Malbrigid’ which appears

on one of the crosses on the Isle of Man. The

name is not a typical Welsh compound, but a copy

of a Goidelic form.[21]

The Irish ‘Mac

Giolla Bhrighde’, or Scottish

‘Mac GilleBrighde’,

meaning servant or devotee of St. Brigid, is

similar.

Hymn to Sant Ffraid

In the 20th century, the poet Ruth Bidgood wrote the Hymn to Sant Ffraid as a radio poem for three voices, commissioned by BBC Radio Wales in conjunction with the Welsh Arts Council and broadcast in April, 1979. In 2006 it was published in Symbols of Plenty by Canterbury Press. It incorporates the Welsh lore about Brigit into the poem, alongside that of Ireland and Scotland and is a beautiful work of exploration and homage. Ruth Bidgood says of the Hymn: "This is an ode to a concocted Celtic saint - concocted in that a real person of whom little is known took on some of the attributes of a previous fertility goddess cum muse and became the centre of a cult which expressed a number of perennial human preoccupations."

Places in Wales connected with Sant Ffraid

Baring-Gould and Fisher give a list of the churches and chapels associated with her:

There are no less than 17

dedicated to her: Dyserth (called also formerly

Llansantffraid), Flintshire; Llansantffraid Glan

Conwy (formerly called also Dyserth), in

Denbighshire; Llansantffaid Glyn Ceiriog, in the

same county. Llansantffraid ym Mechain,

Montgomeryshire [now Powys]; Llansantffraid

Glyndyfrdwy, Merionethshire [now Denbighshire];

St Bride’s, Pembrokeshire, and the noble bay

bears her name as also the haven; Llansantffraid

in Cardiganshire [now Ceredigion];

Llansantffraid Cwmmwd Deuddwr (or simply

Cwmtoyddwr), Radnorshire [now Powys];

Llansantffraid yn Elfael, also Radnorshire

[Powys]; Llansantffraid-juxta-Usk in

Brecknockshire [now Powys]; St Bride’s Major, S

Bride’s Minor and S Bride’s-super-Ely, in

Glamorganshire; Llansantffraid, Skenfrith (Ynys

Gynwraidd), S Bride’s Netherwent, and S Bride’s

Wentloog, all in Monmouthshire. Bridstow in

Ergin (Herefordshire) is called “Lann Sanfreit”

in the Book of Llan Dâv.

To

these may be added the following chapels, now

either in ruins or extinct:

Capel Sant Ffraid, under Holyhead, Anglesey; Capel Sant Ffraid, under Llansantffraid Glan Conwy, Denbighshire; and another under Nevern, Pembrokeshire; and Capel Ffraid, under Llandyssul, Cardiganshire [now Ceredigion]. A conventual foundation of St Ffraid’s is said to have once stood on the Cardiganshire coast, about a mile to the north of Llanrhystud. Llansantffraid is a little to the south of it. Kinnerley Church, Salop, now dedicated to the Blessed Virgin

Francis Jones, in The Holy Wells of Wales, mentions seven wells and a spring associated with Brigit. [23]

Anglesey: unlocated.

Cardiganshire (now

Ceredigion): ‘St Fride’s Well’ south-west of

Ystradmeurig, near Treffynnon.

This well, presently known as Ffynnon Sant Ffraed, is now located in a private garden in the village of Swyddffynnon, Ceredigion. The earliest known record of the well is a 14th century map by William Rees. It is believed it was a watering-hole for monks travelling to

Strata Florida Abbey about 5 miles away, although it may have been connected with an another abbey called Mynachdy Ffynonoer which appears on the same 14th century map. It would also have been used by the bard Ieuan Brydydd Hir who lived in a house on the site of the present building in the early 18th century.

Denbighshire

: a Ffynnon St Ffraid within a quarter of a mile from Llansantffraid Parish Church. [24]Flintshire:

St Bride’s Well, in Disserth parish.Merioneth: Ffynnon Santffraid, a quarter of a mile above the church of Llansantffraid Glyndyfrdwy. [25]

Monmo

uthshire: Two wells – ‘St Ffreid’s Well, Skenfrith where there is a church dedicated to St Bride, and one in Bridewell Wood in Llanvaches Parish, (6 miles south-west of Chepstow). Probably the one which is marked on the OS Map as St. Fraed's Well (SO 462203).[26]Pembrokeshire: There was a Pistyll San Ffraid or Pistyll San Ffred, near the old chapel of St Ffraid, near Henllys, Nevern Parish. The field on the north-west and next to Castell Henllys is called Pant Sant Ffread and the 6 inch OS Map shows a spring there. Jones notes that ‘Capel Sant Ffredde’ is mentioned by G. Owen as a chapel to which pilgrimages were made. [27]

You can see photos with descriptions of many of these churches as they are today on the excellent website Brighid: Goddess and Saint.

There is also a legend attached to the village of Llandre in Ceredigion, some fifteen miles north of Llannon and

about 5 miles north of Aberystwyth, which is also called Llanfihangel Genau'r Glyn (The Church Settlement of Michael at the Mouth of the Valley). Randall Enoch in his Parish History tells of a legend about the building of the church which was said to have been originally intended to be constructed at Glanfrêd (the ‘frêd’ another alternative spelling of Ffraid) on the bank of the Eleri river about a mile north-east of the present church and dedicated to St Ffraid. The walls were built but each morning when the builders came back to start work they had fallen down. Eventually a voice was heard whispering in the wind which told them the church was to be dedicated to St Mihangel (Michael) and built at the mouth of the valley where it is now. Enoch comments that "there may have been two factions, one which favoured building at Glanfrêd, where there may have been a small wooden church dedicated to Brigid, a satellite llan of Llanbadarn Fawr, the other which favoured the present site". [28]There is an old building standing on the site where the church was to be built which is now called Fferm Glanfrêd. Samuel Lewis in A Topographical Dictionary of Wales 1833 notes that “Glanvraed was an old mansion on the left bank of the river Leri, remarkable as the supposed birthplace of the celebrated antiquary, Edward Llwyd, author of the Archaeologia Britannica, and many other works on the natural history and antiquities of Wales”. Llwyd was also the first person to identify and use the term ‘Celtic’ to describe this branch of the Indo-European language family, in 1707. Edward Lluyd’s mother was – interestingly – called Bridget (Pryse).

Fisher and Baring-Gould note that there is a brook called ‘Ffraid’ which runs into the Eleri in North Ceredigion.

Glanfrêd probably means ‘the bank of the Ffraid’ from glan, meaning bank or shore (the other possibility, that it means glân,‘holy’, is less likely), and there is a stream running past Fferm Glanfrêd which arises from a spring near Lôn Glanfrêd (Glanfrêd Lane). It runs down through a marshy woodland, around the caravan site below the farm, and into the river Eleri just beyond it. It is unnamed on the map but it seems at least possible that this is the brook referred to.[29]

Legends of stones being moved when churches were

being built – as well as animals showing saints

where to build them – were fairly widespread.

Holy places needed to be sited carefully. There

is a similar tradition connected with Llansantffraid ym Mechain.

Originally the nearby Foel Hill (which has an

iron-age fort on top of it) was chosen as it was

thought to be closer to God because of its

height. However as soon as building began

the villagers found that the stones had been

moved to a hill on the other side of the road.

They moved them back to Foel Hill, but again

overnight they were moved. The villagers saw

this as the will of God and built the church on

the second site.

St David’s church, Brawdy. ‘Brawdy’ is probably an anglicised form of Welsh ‘breudeth’ which could mean that the original church was dedicated to St Brigit. Alternatively it might mean ‘the house of judgment’ or ‘the house of the brethren’ from the Welsh brawd-dŷ. There is a suggestion that the nave is aligned to the sunrise on St Brigit’s Day, February 1st, and the chancel is aligned to the St David���s Day sunrise on March 1st

.[30]

Brigit in Wales: Words, Stones and Water

The story of Brigit in Wales is woven of words, stones and water. Thanks to the survival of Iorweth Fynglwyd’s cywydd we know something about the tradition of the Welsh Brigit - a composite perhaps of four holy women of that name, rather like Elen of the (Roman) Roads is a composite figure made up of the mythological Elen Luyddog; Elen Ferch Eudaf, wife of the Roman Maximus and St Helena, the mother of Costantine the Great. [31] The poem gives us tantalising hints of certain stories of Brigit and her miracles not recorded in Ireland, as well as the uniquely Welsh miracle of the rushes turned into sparlings. We learn that her feast day, February 1st was established by Jesus himself, the day before Candlemas, and was honoured in Wales. Other poems and records tell us that the custom of St Brigit’s Ale was a renowned part of the festival in Wales. Folk custom confirms the story of the rushes turned to sparlings and the connection with fish appears again when we learn that the fishermen used to pray in her chapel for success with their catch and that their prayers appear to have been answered.

Words have given us the stories and Brigit's name lingers. The stones of the many churches dedicated to Sant Ffraid place her firmly in the landscape, making sure she is rooted in the holy places of Wales where people still worship and see her image. The wells, carefully documented by Francis Jones, show us faint traces of other sacred places where people told stories of the holy men and women of this land and where their miracles could still be sought through the medium of life-giving water. She is remembered in the great waters of Wales: by legend in the rivers Conwy and Dyfi; by name in the Bay of St Bride in Pembrokeshire where the Welsh land embraces the Irish Sea. And last but not least in the river Braint on Anglesey which retains the Welsh version of her name and remembers perhaps the older story of a goddess of sovereignty underlying the Christian saint and rippling down the ages to our present time.

Millenium Cross commemorating St Bride

at Trearddur Bay, Anglesey

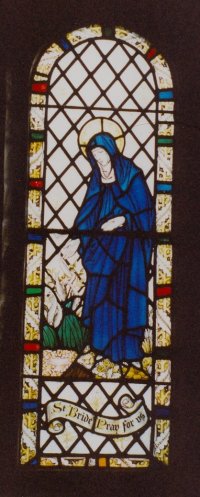

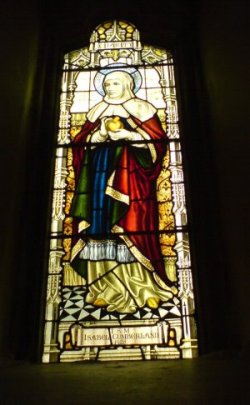

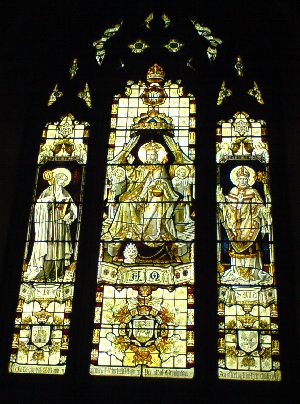

Pictures of St Ffraid in Stained Glass Windows

1. Sant Ffraed, Leian. Llansantffraed Church, Llanon, Ceredigion

2. St Bride, Pray For Us, St Non's Chapel, near St David's, Pembs.

3. St Ffraid with apple, commemorating Charity. Llansantffraid ym Mechain, Powys

4. Altar window showing St Bride on the right hand of the king of heaven. Llansantffraid ym

Mechain

Main sources and recommended further reading

Baring-Gould,

Sabine and Fisher, John (1907-1913)

Lives of the British Saints, 4 vols, London:

Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion

Henken, Elissa (1987) Traditions of the Welsh Saints, Cambridege: D. S. Brewer

Jones, Francis (1954) The Holy Wells of Wales, Cardiff, University of Wales Press

References

Jones, Howell Llewelyn and E. I. Rowlands, eds., (1975) Gwaith Iorwerth Fynglwyd, Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, p 94. A copy also appears in Williams, Robert (1835) History and Antiquities of Aberconwy Denbigh, pp. 198-200 Available online at: http://books.google.co.uk/books Last accessed 16th October 2010 Baring-Gould, Sabine and Fisher, John (1907-1913) Lives of the British Saints, 4 vols, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, vol 1, p. 264 – 288[3] Morris, Lewis (1878) Celtic Remains, London, p. 386. Available online at: http://books.google.co.uk/books p.386 Last accessed 16th October 2010

Baring-Gould, Sabine and Fisher, John (1907-1913) Lives of the British Saints, 4 vols, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, vol 1, p. 288Henken, Elissa (1987) Traditions of the Welsh Saints, Cambridege: D. S. Brewer, pp 161-167

Quoted in Henken, Elissa, (1987) Traditions of the Welsh Saintsi> Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, p 167

Roberts, Askew and Woodall, Edward (1902) Gossiping Guide to Wales: North Wales and Aberystwyth Kent: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, p.213

Saint Ffraid and Millennium Cross, Trearddur Bay (Anon., 2008-2012) Available: http://www.anglesey-today.com/saint-ffraid.html Last accessed 16th October 2010.

Koch, John (2006) Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia 5 vols, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO Ltd, p.287 See also: Gruffydd, Astudiaethau ar yr Hengerdd 25-43 (Moliant Cadwallon; Gofara Braint)

Henken, Elissa, Traditions of the Welsh Saints (1987) Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, pp 161-167 See also

Walley, Noel (2008) Saint Ffraid, St Mary’s Prayers, and Bardsey Island.

Available http://www.greatorme.org.uk/bryncroes.html Last accessed 16th October 2010

[11] Baring-Gould, Sabine and Fisher, John (1907-1913) Lives of the British Saints, 4 vols, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, vol 1, p. 286

[13] Dorothy A. Bray, Dorothy A. (1987) ‘The Image of St. Brigit in the Early Irish Church’, Etudes Celtiques, 24, pp.209-15

[14] T. Gwyn Jones., T. Gwyn. ed. (1926) Gwaith Tudur Aled Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, p 100

[15] Fortin, David., 46fortin@cua.edu, 2002 St Brigid’s Beer. [email] Message to Celtic-L, sent Monday 10 June, 22:20 Available at https://listserv.heanet.ie/cgi-bin/wa?A2=celtic-l;9jge0A;200206102220320400 [Accessed 16th October 2010] Quoted with permission of the author. Quoted in Simon Young, Simon (2001) ‘St Brigit in a Medieval Welsh Poem’, Peritia, vol 15, p 279

See footnote 39 on p 22 of Simon Young, Simon (1988) ‘Donatus Bishop of Fiesole (829-76) and the Cult of St Brigit in Italy’, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies, 35, pp. 13-26

ibid., p 26

Johnston, Dafydd. ed. (1995) Gwaith Lewys Glyn Cothi, University of Wales Press, p 238. I am grateful to Dr George Jones for helping to tease out the meaning of these lines.

Williams, John Ab Ithel. ed., Pugh, John. ed and transl., (1993) The Physicians of Myddfai facsimile edition, Felinfach: Llanerch publishers, pp 438-9 Baring-Gould, Sabine and Fisher, John (1907-1913) Lives of the British Saints, 4 vols, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, vol 1, pp 285

Baring-Gould, Sabine and Fisher, John (1907-1913) Lives of the British Saints, , 4 vols, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, vol 1, p. 283

Jones, Francis (1954) The Holy Wells of Wales, Cardiff, University of Wales Press

E. Lluyd, Parochalia (1695-98), Arch. Cam. Suppl. 1909, 1910-11, vol. I, p.35

ibid, vol. ii, p.47

M.N.J., (1926) Bygone Days in the March Wall of Wales, London, p.71

George Owen, (1892-1936) The Description of Pembrokeshire, vol ii, London p.509

Enoch, Randall Evans OBE. Llanfihangel Genau'r Glyn - A Church History. Published by the author in June 2002, p 172

I am grateful to Greg Hill for drawing my attention to this legend and providing the information.

[30] Davies, Damian Walford., Eastham, Anne., (2002) Saints and Stones Llandysul: Gomer Press pp. 90, 92

Henken, Elissa, Traditions of the Welsh Saints (1987) Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, p 13