Brigit's Forge Website

Brigit the Goddess

Contact

Blogs

Musings from Gelli Fach

Storing Magic

The Goddess in Archaeology

The Romans

equated

Brigantia with

Minerva, a

goddess of war,

wisdom and

crafts. There is

evidence of this

from a statue at

Birrens in

Dumfriesshire

which shows her

with Minerva’s

symbol of the Gorgon’s head on

her breast, a

mural crown, a

spear and the

globe of

victory.

Modern scholars accept the link between Brigit and Brigantia who was the tribal protector of the Brigantes, a powerful tribe in the north of England. She was a bringer of fertility and prosperity, a patron of the arts and associated with healing. On the continent there was a tribe known as the Brigantii near Bregenz in Austria and since we know that Minerva was honoured there it is reasonable to assume that Brigantia was also a Celtic goddess of that area and that tribe.

There are seven inscriptions to Brigantia, in two of them she is referred to as ‘dea Victoria’ which possibly reflects her function as tribal protector. In another she is called ‘Nympha Brigantia’ and invoked for healing (‘pro salute’). In yet another she is described as ‘Caelestis Brigantia’ or heavenly Brigantia which evokes images of her as both exalted and wonderfully pleasing, and suggests that she has a place in the heavens perhaps as the sun which is a heavenly body. (2)

There are also inscriptions to a goddess of East Gaul called Brigindo whose iconography implies that she was a goddess of healing, crafts and fertility, similar to Brigantia.

These then are the archaeological indications that Brigit was known both on the Continent and in Britain as a goddess of fertility, crafts and healing.

The Goddess of the Tuatha De Danaan

To learn of Brigit as an Irish goddess we must go to the texts written down in Christian Ireland. Probably the first mention of Brigit as goddess is in Cormac’s Glossary written in the 9th century - a glossary of gods, goddesses, practices and folklore gathered from written and spoken sources. Cormac says:

“Brigit i.e. a poetess, daughter of the Dagda. This is Brigit the female sage, or woman of wisdom, i.e. Brigit the goddess whom poets adored, because very great and very famous was her protecting care. It is therefore they call her goddess of poets, by this name. Whose sisters were Brigit the female physician (woman of leech craft), Brigit the female smith (woman of smith work), from whose names with all Irishmen a goddess was called Brigit.”

One version of this glossary also gives an etymology for Brigit: “Brigit, then, breo-aigit, breo-shaigit ‘a fiery arrow’.” Modern scholars have shown that this is a false or folk etymology, the name Brigit actually comes from old Celtic *briganti which in turn derives from Indo-European *bhrghnti. Sanskrit has an exact cognate brhati which means ‘the exalted one’. (3 )However, folk etymology - the association of words that sound alike, and the explanation of names by this method - makes connections where reason would find none (much like poetry) and in these connections we sometimes discern deeper layers of truth. In many ways ‘fiery arrow’ is a fitting name for Brigit since in one image it conveys the idea of the bright flame that has come to be associated with her, along with a sense of her directness, her ability to get straight to the point and the force of her energy, which many working with her today will recognise. The rays of the sun may also be described as fiery arrows.

This, then, is the one of the first glimpses we have of the goddess Brigit, daughter of the Dagda, the good god, sometimes the father god of the Tuatha De Danaan. She is seen here for the first time as a triple goddess, of poetry, smithcraft and healing (not as maiden, mother and crone) and she was either so often invoked that it appeared to Cormac that all goddesses were called Brigid, or else the name Brigit was actually a title and not a name per se. It is interesting to see that what is emphasised here, in these few lines written a thousand years ago, is how much she was loved because her protecting care was so great - already we have a picture of a goddess who is actively involved with humankind, who is so caring that she evokes much love.

Another reference to her as a goddess is in the 12th century Book of Invasions of Ireland which gives the mythological history of Ireland. Here it is said:

“Brigit the poetess, daughter of the Dagda, she had Fe and Men, the two royal oxen, from whom Femen is named. She had Triath, king of her boars, from whom Treithirne is named. With them were, and were heard, the three demoniac shouts after rapine in Ireland, whistling and weeping and lamentation. She had Cirb, king of the wethers, from whom Mag Cirb is named.”

It is interesting that she is here associated with kingship - she has royal oxen, a king of the boars and a king of the wethers. The king of her boars, Triath, is the Twrch Trwyth (since the names are cognate ) who appears in the story of Culwch and Olwen in the Mabinogion. The Twrch Trwyth is the boar from Ireland which Culwch and his companions hunted. They needed to get from him a comb and shears to untangle the beard of the giant Ysbaddaden, father of Olwen, whom Culwch wished to marry. The Twrch Trwyth is the son of the ruler Taredd, a king himself who was changed into a boar by God because of his sins.

The boar is an appropriate animal for Brigid since in the Celtic tradition it symbolised aggression which was needed by the warrior and was a favourite ornament for warriors’ headgear. For, as we have seen, she is sometimes depicted as a tribal protector and warrior goddess in her guise as Brigantia. Evidence from Celtic coins and carvings also links boars with sun gods and solar symbols and the pagan Brigit is thought to have been a goddess of fire and of sun. In Irish tradition the White Boar of Marvan was a herdsman, a physician, a messenger and a musician - activities connected with Brigit as goddess of poetry and healing.

A poem by St Broccan about Saint Brigit describes her association with the boar, (and this is again mentioned in the life by Cogitosus). There is here, perhaps, a reminder of Triath, the king of the boars who was with the goddess Brigit.

“A

wild boar

frequented her

herd,

To the north he

hunted, the wild

pig;

Brigit blessed

him with her

staff,

And he took up

his stay with

her swine.”

The other animals mentioned with her in the Book of Invasions are domesticated animals - oxen and wethers - pointing to her function as a fertility goddess and protector of domestic animals. Later on, as Saint Brigit, we shall see that she is particularly associated with cows and sheep, able to milk her cows three times and to generally create abundance, enough to feed all who came to her.

We hear of Brigit again as one of the Tuatha De Danaan in the story of the Battle of Maigh Tuiredh (12th century but based on 9th century material) which tells of the conflict between the Tuatha De Danaan and the previous inhabitants of Ireland, the Fomorians. Here she is presented as a mediator (a liminal being) being married to the Fomorian king, Bres, although she is the daughter of the Dagda of the Tuatha De Danaan. Their son, Ruadan wounds the smith, Goibniu, of the Tuatha and is killed by him. We are told:

“Bríg came and keened for her son. At first she shrieked, in the end she wept. Then for the first time weeping and shrieking were heard in Ireland. (Now she is the Bríg who invented a whistle for signalling at night.)”

This

reflects the

piece in the

Book of

Invasions “With them were

and were heard

the three

demoniac shouts

after rapine in

Ireland,

whistling and

weeping and

lamentation.”

So Brigit is

not depicted as

a warrior

goddess like the

dark Morríghan

who is

associated with

the destructive,

gory side of

war. She gives

protection to

those in her

care and laments

for those who

die. She is a

mother goddess

who weeps for

her fallen son

and perhaps

because every

warrior is some

mother’s son she

does not glorify

or exult in war.

Possibly there

is here the seed

of St Brigit’s

later

personification

as the Mary of

the Gael,

fostermother,

sometimes even

the mother, of

Jesus, another

mother who wept

at the death of

her son. Yet it

needs to be born

in mind that the

texts mentioned

above are

actually later

than the texts

detailing the

life and

miracles of St

Brigit and it is

possible that

the authors or

scribes of the

texts were

influenced by

the later figure

of the saint.

The Goddess in Ireland Today

There is little trace of Brigit the ancient goddess in Ireland now, she has been almost totally superseded by the figure of the saint. One place where her presence does linger, however, is in the parish of Knockbride in Co. Cavan. There is a hill there called Knockbride (Hill of Bride) on the top of which is an old well and fort, and there are two small lakes, Upper and Lower Lochbride. Many artefacts have been recovered from this area, including the famous triple Corleck Head, now in the National Museum in Dublin and a stone head, thought to be that of Brigit, now lost.

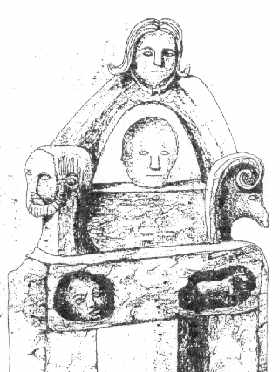

This picture

shows the shrine

from Knockbride

with the

supposed

head of

Brigit (wearing

a torc) at the

top, the Corleck

head directly

beneath her and

the ram's head,

the bearded

head, the

one-eyed head

and the horse

beneath that.

Only the Corleck

head and the

bearded head

have survived;

both are now in

the National

Museum in

Dublin.

It seems certain that Brigit was worshipped here in the past, and probably, in some form, until the 19th c. The stone head survived until a parish priest, Fr. Owen Reilly, (1840-44) removed it. According to local tradition, handed down from generation to generation, Fr. O' Reilly took it from the East end of the parish to the West, where a new church was being built. He claimed that Brigit's head jumped out of the carriage and into Roosky lake where she disappeared for ever.

Another tradition records that he asked for help unloading a stone near dusk at the site of the new church and that she may therefore have been buried in the foundations of the church.(4 ) It would be nice to think that the head has not left the parish but lies in the waters of the lake or deep in the earth. Certainly, as St Brigit, her presence is still felt and the new church of West Knockbride bears a statue of her, enshrined in a niche high up, exalted, in the front of the building.

Church of West Knockbride

© Hilaire Wood 1999