Brigit's Forge Website

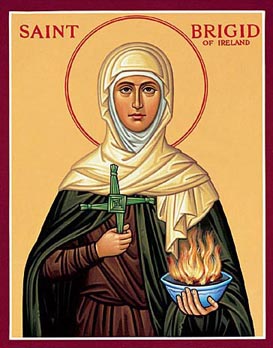

Brigit the Saint

Contact

Blogs

Musings from Gelli Fach

Storing Magic

Brigit's Miracles and her Connection With Ale

Brigit's Connection with Water

Brigit: Virgin, Mother, Spinster, Lesbian

Brigit in the Kitchen and Commanding Kings

Brigit Associated with the Number 8

The Lives of St

Brigit

Most of the remaining picture of Brigit is made up of

the legends and stories about St Brigit of

Ireland in which,

it has been assumed, there are elements of

an underlying pagan deity.

It could be, however, that St Brigit never existed since there is no historical evidence to support that she did. The earliest reference we have comes from around 600 AD in an origin story for the Fotharta sept or clan, where it is claimed that she was one of the sept and is referred to as ‘truly pious Brig-eoit’, and ‘another Mary’. Dáithi Ó hÓgáin records that the rise of her cult was a result of the rise to power of a new sept in Leinster, the Uí Dhúnlainge. As the wife of the clan leader was a member of the Fotharta and his brother was the bishop of Kildare it was in his interest to promote the cult of Brigit.(5) The Vita Brigitae of Cogitosus is thought to have been written no later than 650 AD, at the request of the Kildare church which is described in it as “the head of almost all the Irish Churches with supremacy over all the monasteries of the Irish and its paruchia extends over the whole land of Ireland, reaching from sea to sea.” According to another scholar the leaders of Armagh were promoting St Patrick and had allied themselves with the ruling families of Meath in an attempt to dominate the whole island.(6) The promotion of Brigit and the see of Kildare rivalled this.

Although there is some controversy about it, the

Cogitosus life

(7)

is now thought to be about a century

earlier than the so-called first life of Brigit,

Vita Prima Sanctae Brigitae (Vita 1)(8).

This makes it a very early text and it is

distinguished by being the first hagiography

(life of a saint) in Hiberno-Latin, although two

lives of Patrick and one of Columbus also belong

to the 7th c. Perhaps it was successful as a

propaganda exercise and the lives of Patrick and

Columbus were hurriedly composed to compete with

it. So the early Christian church may have

appropriated the goddess Brigit and dressed her

in Christian clothes - although underneath, so

to speak, she remained a pagan goddess - in

order to win over the pagan Irish who loved

Brigit so much. Certainly Cogitosus does not

give an account of a real person although she

had lived only a hundred years before. His Vita

is made up of the many miracles she is said to

have performed and stresses both her faith and

her virginity. But it is also possible that she

was a living person, a Christian woman called

Brigit who was either a reincarnation of the

goddess or was seen to be so by the Irish

people.

We have seen little so far that depicts Brigit

as a goddess of fire and the sun apart from the

reference to ‘Caelestis Brigantia’, the folk

etymology connecting Brigit with a fiery arrow,

and her association with boars - all rather

tenuous. In the lives of the saint, however,

images of fire and sun abound. In Cogitosus’

Vita we hear the famous story of her hanging her

cloak on a sunbeam, apparently a motif borrowed

from an apocryphal Continental story about

Christ as a child:

“As she was grazing her sheep in the course of

her work as a shepherdess on a level grassy

plain, she was drenched by very heavy downpour

of rain and returned to the house with her

clothes wet. There was a ray of sunshine coming

into the house through an opening and, as a

result, her eyes were dazzled and she took the

sunbeam for a slanting tree growing there. So,

she put her rain soaked clothes on it and the

clothes hung on the filmy sunbeam as if it were

a solid tree.”

The sun and fire are particularly stressed in

the 8th c lives of the saint which were based on

older sources and may reflect lore relating to

the goddess Brigit.

The life of St Brigid in the Book of Lismore,

which is generally the same as Colgan’s Tertia

Vita and the life in the Lebar Brecc

(9) connects her strongly with them both. A

wizard prophecies, on hearing the sound of Dubthach’s chariot, that Dubthach’s bondmaid

Broicsech will give birth to a daughter

“conspicuous, radiant, who will shine like a sun

among the stars of heaven.” Later a holy man

sees a flame and a pillar of fire coming from

the house where Broicsech, pregnant with Brigit,

is sleeping, and after she is born, the child

Brigit is asleep in the house one day when her

mother has gone milking and the neighbours

behold it ablaze “so that one flame was made

thereof from earth to heaven.” When they went to

rescue her they found that nothing was burnt.

Later, when Brigit is a young woman and goes to

take the veil from Bishop Mel, a fiery flame

rises from her head to the roof-ridge of the

church “and it came to pass that the form of

ordination was read out over her.” Bishop Mac-caille

declared that a bishop’s order could not be

conferred on a woman but Bishop Mel replied that

he had no power in the matter “That dignity has

been given by God to Brigit.” So Brigit became

an archbishop and appointed bishops herself. Her

soul was said to be “like a sun in the heavenly

kingdom” and at Doomsday she will rise “like a

shining lamp in completeness of body and soul”.

The Life of Saint Brennain in The Book of

Lismore asserts that Bríg

(10) was his own sister and that her

foster-father used to see her countenance “as it

were the radiance of the summer sun”. The hymn

‘Brigit Be Bithmaith’

(11)

begins with a powerful invocation which

describes her as the sun-:

“Brigid, excellent woman,

Flame golden, sparkling,

May she bear us to the eternal kingdom,

(She), the sun, fiery, radiant! "

Yet it must be said that it was common for

saints to be associated with fire and sun

imagery. The Life of Ciarán of Clonmacnois in

the Book of Lismore also gives the story of a

wizard who prophecies from hearing the noise of

the chariot, “the noise of chariot under king,”

that Ciarán, who is in the woman’s womb, will be

a mighty king and “as the sun shineth among the

stars of heaven, so will he shine on earth in

miracles and marvels that cannot be told.” On

the night of Brenainn’s birth the bishop Eirc

saw a wood under one vast flame, and Patrick as

a child was able to produce five sparks of fire

from the five drops of water trickling from his

fingers and thereby vanquish a flood and make

the fire blaze once more. What we are seeing

here is a general association between the sun,

fire and beings of the Otherworld or of

supernatural powers. This is in keeping with the

observation that the word for 'god' in many

Indo-European languages stemmed from IE deivos

which is connected etymologically with the verb

div, dyu,' to shine', indicating that early IE

thought connected divinity with luminosity.

However, this imagery is applied to varying

degrees and Brigit does have it heaped upon her,

so to speak, while Columbus, for instance, has

almost none of it, at least in the Book of

Lismore.

We must look elsewhere to overlay the thin layers of evidence that begin to build up into the vibrant and glowing picture of Brigit as sun goddess which is generally accepted today. Another layer is made up by Gerald of Wales’s account of his visit to Kildare in 1185. Back to top

“In Kildare, in Leinster, which the glorious

Brigid has made famous, there are many miracles

worthy of being remembered. And the first of

them that occurs to one is the fire of Brigid

which, they say, is inextinguishable, but that

the nuns and holy women have so carefully and

diligently kept and fed it with enough material,

that through all the years from the time of the

virgin saint until now it has never been

extinguished. And although such an amount of

wood over such a long time has been burned

there, nevertheless the ashes have never

increased.

Although in the time of Brigid there were twenty

servants of the Lord here, Brigid herself being

the twentieth, only nineteen have ever been here

after her death until now, and the number has

never increased. They all, however, take their

turns, one each night, in guarding the fire.

When the twentieth night comes, the nineteenth

nun puts the logs beside the fire and says: “Brigid,

guard your fire. This is your night.” And in

this way the fire is left there, and in the

morning the wood, as usual, has been burned and

the fire is still lighting.

This fire is surrounded by a hedge which is

circular and made of withies, and which no male

may cross. And if by chance one does dare to

enter (and some rash people have at times tried

it) he does not escape the divine vengeance.

Only women are allowed to blow the fire, and

then not with the breath of their mouths, but

only with the bellows, or winnowing forks....

At Kildare an archer of the household of earl

Richard crossed over the hedge and blew upon

Brigid’s fire. He jumped back immediately, and

went mad. Whomsoever he met, he blew upon his

face and said: “See! That is how I blew on

Brigid’s fire.” And so he ran through all the

houses of the whole town, and wherever he saw a

fire he blew upon it using the same words.

Eventually he was caught and bound by his

companions, but asked to be brought to the

nearest water. As soon as he was brought there

his mouth was so parched that he drank so much

that, while still in their hands, he burst in

the middle and died. Another who, upon crossing

over to the fire, had put one leg over the

hedge, was hauled back and restrained by his

companions. Nevertheless the leg that had

crossed perished immediately with its foot. Ever

afterwards (while he lived) as a consequence he

was lame and an imbecile.”

(12)

This account points

to a more ancient site where there may have been

a temple of the goddess Brigit in which an

eternal flame was tended by 19 priestesses and

dedicated to women’s mysteries, forbidden to

men. The power and veneration of the site is

certainly attested to by the fact that the flame

was kept alight for so many centuries. It was

extinguished in 1220 by Bishop Henry of Dublin

in an attempt to stamp out pre-Christian

practises, and the abbess was raped and unable

to continue in her role. However the flame was

eventually relit and all continued as before

until the Reformation of the 16th c when the

flame was put out and the monastery destroyed.

All that remained of the flame house next to St

Brigid’s Cathedral in Kildare was the

foundations, until recently when it was rewalled

to show where it had been. However, in 1993

Sister Mary Minehan of the Order of Brigidine

Nuns (established in 1807) relit Brigit’s flame

in Kildare.

The name Kildare,

or Cill Dara, means ‘Church of the Oak’ and this

association of the site with the sacred oak of

pagan Ireland is an important indication that

there was once a pre-Christian sanctuary there.

Back to

top

Brigit's Miracles and Her Connection with Ale

The many miracles

St Brigit performs are reminiscent of those of

Jesus. She turns water into ale and stones into

salt; she makes a little food become enough to

feed all the people present; she performs many

healing miracles; she looks after and heals

lepers and the poor, giving away her father’s

wealth, even his sword. This accords with her

divine status, in a sense raising her to the

same level as the son of God - the goddess

Brigit was, after all, the daughter of the

father god, the Daghda. It is interesting to

note that two of the miracles recount her

turning water into ale - unlike Columba who

turns water into wine - and there is one miracle

in which she ensures enough ale for 17 churches

even though there has been a dearth of corn and

malt.

Saint Brigit or Santes

Ffraid who is commemorated in Wales in a 16th

century cywydd

(Welsh poem in a special metre) by Iorwerth

Fynglwyd seems to be an amalgamation of several

St Brigits - Brigit of Cill-Muine, Brigit of

Kildare, the Swedish saint and a Brigit from

Gwynedd in North Wales. In Wales, there was

apparently a custom of ‘cwrw

Sant Ffraid’

(St. Brigit’s Ale) mentioned in the Red Book of

Asaph (‘quadam

consuetudo vocata Corw Sanfrait)(13),

and St Brigit’s Day in Wales is connected with

‘drink’ -

“Digwyl san ffraid

ydoedd fenaid

i bydd parod pawb ai wirod.”

(14)

(St Brigit’s day it

was, my soul, everyone will be ready with his

drink.)

Lady Gregory gives

the following ‘Wishes of Brigit’ in which ale

features:

“I would wish a

great lake of ale for the King of Kings; I would

wish the family of Heaven to be drinking it

through life and time.”

“I would wish the

men of Heaven in my own house; I would wish

vessels of peace to be giving to them.

I would wish

vessels full of alms to be giving away; I would

wish ridges of mercy for peacemaking.

I would wish joy to

be in their drinking; I would wish Jesus to be

here among them.”

Travelling in

Ireland recently, I noticed several pubs in Co.

Clare had Brigit’s crosses hanging behind the

bar.

St Brigit's Shrine at

Faughart

It is interesting to connect this emphasis on ale with the folklore view of the Irish poet as someone who could not make a song when sober. Intoxication is connected with a state of being excited or elated beyond the normal and the imbibing of certain liquids is one way to achieve this. There may be an echo behind these folklore traditions of ancient Irish ideas that poetic skill was obtained by drinking or eating substances which contained imbas forosnai, knowledge which illuminates. Many ancient texts connect poets with the word meisce which can mean ‘in a mental ferment’ as well as ‘intoxicated’, and often describe them as being heated or having inflamed faces while composing. (15) Back to top

But ale is also connected with the giving of kingship and more than one scholar has suggested that Brigit is a Christian version of Queen Medb of Connacht, whose name means ‘she who intoxicates’.(16) Brigit is said to have been born at Faughart

which had associations with Medb (the Cooley Peninsula may be seen from the old hilltop graveyard at Faughart where there is a well dedicated to Brigit). Medb has mythic associations with the goddess of sovereignty; in the stories she has many lovers and it appears that sexual union with her confers kingship upon them. But also in the old Irish tales kingship is sometimes conferred by drinking dergfhlaith, red ale or red sovereignty (there is a pun on the Irish word for ale, laith, and sovereignty flaith) so it is possible that Brigit’s connection with ale points not only to her functions as a mother goddess of plenty and fertility and a goddess of poetry, but to her function as sovereignty goddess. It has been convincingly argued that the Welsh word for king, brenin, originally meant consort of the goddess *Briganti and that its first use was in reference to the male leaders of the Brigantes. The title occurs on a Continental Celtic coin (17) which depicts a veiled female head on one side and a bull with laurel crown on the other.

The goddess of sovereignty very often has two guises - that of a hag and then when the young hero agrees to have sexual union with her, that of a beautiful young woman. There are tantalising traces of this dual nature in lore relating to Brigit. Lady Gregory says of the goddess Brigit that she had two faces, one that is young and comely and one that is old and terrible. In Scottish folklore Bride, the bringer of Spring, is closely associated with the hag, the Cailleach of the stark Winter, and some people assert that they are two sides of the same being.

More than one of the lives of the saint describe an incident in which Brigit plucks out her own eye rather than marry - by this act making herself not only unattractive, but also haglike (although she is able to heal herself by using the waters of a well.) Although the Irish scholar Dáithi Ó hÓgáin asserts that this motif was borrowed from Continental hagiography about St Lucy, another saint connected with light, it is still interesting that it is associated with Brigit. Back to top

We have looked at Brigit's connection with fire and the sun, but she is also connected with water. Celtic goddesses are often connected with rivers and Brigit is no exception. The British goddess Brigantia of the Brigantes of northern Britain was linked with river and water cults and her name is remembered in the Braint on Ynys Môn (Anglesy), the Brent in Middlesex and rivers in Munster in Ireland.

Many sacred wells are dedicated to her and are still used and venerated today. At Faughart, her birthplace there is not only a well but also a sacred stream which now has the stations of the cross positioned along it.

At Liscannor on the Burren a pilgrimage to the well used to be undertaken at Lughnasad, this has now moved to August 15th.

At Kildare there are two wells dedicated to her - one still very much in use, the other, by the side of the road, is rather neglected although a few rags on the trees behind it give evidence that it is still being visited [in 1999].

Lesser known

Brigit's Well at

Kildare

Eyes

were

connected with both the sun and with water (the

sun on and in water was seen as a powerful

healing agent), and not surprisingly many wells

had the reputation of curing eye problems.

The preface to the

hymn Brigit Be Bithmaith gives one of the

suggested authors as Columcille and said that he

composed it when he went over the sea and was

caught in Breccan’s Cauldron, a dangerous

expanse of water. It was to Brigit he turned,

beseeching her that calm might come to him, thus

acknowledging her superior power over that

element.

In the life in the Book of

Lismore

(18)

a river rises up while

two lepers, one haughty and one humble, are

driving a cow she has given them across. Brigit

herself may have caused the river to rise up and

certainly, through her blessing, the humble

leper is saved. Cogitosus gives a story in which

she, (through God’s will and power, of course)

diverts a river. The people of her weak

tuath

who had been forced by a strong and arrogant

tuath

to work on the most difficult stretch of

road-building through a place where a river ran,

found their work made easier when the river is

miraculously moved.

Another aspect of

her power over water has already been mentioned

in Gerald of Wales’ account of his visit to

Kildare. He tells of the archer who blew on

Brigit’s fire which was forbidden to men and

then goes mad, running through the town blowing

in the faces of people he met. After he is

caught and bound he asks to be taken to water to

satisfy his thirst but his mouth is so parched

that he cannot stop drinking and dies by

bursting in the middle. We are reminded of the

cupbearers in the Second Battle of Maigh Tuired

who also possess magical powers connected with

water and use it against the enemy:

“And you,

cupbearers,” said Lugh, “what power?”

“Not hard to say,”

said the cupbearers, “We will bring a great

thirst upon them, and they will not find drink

to quench it.”

Brigit is here able

to use the destructive power of both fire and

water. And having this power, she also has the

ability to give protection against death by fire

and water. The Genealogy of Bride from Scottish

tradition refers to this ability of Bride to

give protection from the threefold death

described in early Irish literature.

The Descent of Bride

The genealogy of the

holy maiden Bride,

Radiant flame of gold,

noble foster-mother of Christ.

Bride daughter of Dugall the brown,

Son of Aodh, son of Art, son of Conn,

Son of Crearer, son of Cis, son of Carmac, son

of Carruin.

Every day and every

night

That I say the

genealogy of Bride,

I shall not be killed,

I shall not be harried,

I shall not be put in

cell, I shall not be wounded,

Neither shall Christ

leave me forgotten.

No fire, no sun, no moon

shall burn me,

No lake, no water, nor sea

shall drown me,

No

arrow of fairy, nor dart of fay shall wound me,

And I under the

protection of my Holy Mary,

And my gentle

foster-mother is my beloved Bride.

Brigit: Virgin, Mother, Spinster, Lesbian

Although the

goddess Brigit is, as we have seen, a mother

goddess, in the life of the saint she is

decidedly single and her virginal state is

stressed, particularly in the life by Cogitosus.

Christianity, while restricting and degrading of

women in many respects (there was a debate in

Macon in 900 as to whether women had souls or

were like animals and the single vote which

tipped the outcome in women’s favour was said to

have been cast by the Celtic bishops) did give

them an alternative to having to undergo the

rigours of childbirth and the rearing of many

children. Brigit’s stepbrother remarked to her

one day that “ill-used was her eye” that it

would not lie next to a man on the pillow. Her

father decided to marry her to a man she did not

like and rather than do so she plucked her eye

out so that it hung on her cheek. Her father and

brothers were horrified and declared that she

would never have to marry anyone she didn’t want

to, whereupon she put her eye back in its socket

and it was healed. This story illustrates that

Brigit was her own woman, not willing to submit

to marriage and the dominance of a husband.

Yet people do

speculate in our time about whether Brigit

remained single and some like to think that she

had a secret relationship with Conleth, her

bishop. Perhaps it is the glowing description

that Cogitosus gives us of their union that

provokes this speculation:

...she sent for

Conleth, a famous man and a hermit endowed with

every good disposition through whom God wrought

many miracles, and calling him from the

wilderness and his life of solitude, she set out

to meet him, in order that he might govern the

Church with her in the office of bishop and that

her Churches might lack nothing as regards

priestly orders. Thus, from then on the anointed

head and primate of all the bishops and the most

blessed chief abbess of the virgin governed

their primatial Church by means of a mutually

happy alliance and by the rudder of all the

virtues. By the merits of both, their episcopal

and conventual see spread on all sides like a

fruitful vine with its growing branches and

struck root in the whole island of Ireland. It

has always been ruled over in happy succession

according to a perpetual rite by the archbishop

of the bishops of Ireland and the abbess whom

all the abbesses of the Irish revere.

On a more cynical

note it may be suggested that the imagery of a

fruitful union was used purposely to promote the

see of Kildare (much as present-day political

leaders in the West like to promote an image of a

happy family). Cormac's description of the

goddess Brigit "whom all poets adore" rather

echoes the description of St Brigit as one "whom

all the abbesses of the Irish revere".

There is also speculation that she had a lesbian relationship since she was said to have shared her bed with a pupil of hers called Darlugdach. Peter Berresford Ellis, in his book Celtic Women, asserts that she showed intense jealousy towards her in that when Darlugdacha became attracted to a young warrior, she punished her by making her walk in shoes filled with burning coals. Ellis does not cite his source for this and in trying to track it down I have not been able so far to find a published translation of a Life in which the story appears, but the incident is referred to by R.A.S. Macalister, translator of the Book of Invasions of Ireland, in an article in Man 63 (August 1919). His version is this:

Brigid had a pupil, Dar-Lugdach by name, who used to sleep with her. The eyes of Dar-Lugdach chanced one day to fall on a certain man, for whom she was smitten with unholy love. Waiting till her superior was asleep, she rose to join him; but she was suddenly oppressed with a great perturbation of mind, between love and fear. In her distress she prayed, and an angel came down with the following counsel, which she followed: To fill two shoes with hot coals, and to walk shod therewith. So the fire extinguished the fire of her ardour, and the pain conquered her pain; and she returned to her couch. On the morrow Brigid commended her, promised her exemption for the future from the fire of desire in this world and the fire of hell in the next; then she blessed her feet, and the burns were healed leaving no trace.

In this version, whatever the truth about their relationship, Brigit is cleared of forcing Darlugdach to walk with coals in her shoe as a punishment. I wonder if Ellis actually found this story in Mary Condren's The Serpent and the Goddess, which he does cite, and misinterpreted her when she said "...Darlugdacha was said to be 'Brigit's pupil, who used to sleep with her' and who committed the great sin of looking at a soldier. As penance she filled her shoes with hot coals..." Condren here gives Macalister as her source so presumably she does not intend to mean that Brigit imposed this penance, the 'she' she refers to being Darlugdacha herself.

Whatever the truth

may have been about Brigit's private life, what is interesting

here is her universality and the way that people

are moved to speculate about her and, perhaps,

to read into the stories things about her with

which they may identify. In this way she is

brought closer to us, and is able to serve in

many respects as a role-model. A lover of women,

a strong single woman, a woman in happy and

fruitful relationship with a man - she becomes

all things to all women.

Even though a

virgin saint, she still manages to take on the

attributes of a mother. There are stories of her

being the fostermother of Jesus: in Scottish

tradition she is said to have been present at

his birth and to have blessed him with three

drops of water on his brow. The fosterparent was

very important in Celtic society, almost more

important than the actual parents, and commanded

obligations and duties. No wonder it was said

that whatever St Brigit asked for from God was

granted! In another story it is said that in

order to divert Herod’s men away from him so

that he could make his escape to Egypt with his

mother, Mary, she put a crown of candles on her

head and dancing away, led them in another

direction. The motif of this story does not

appear elsewhere in folklore and appears to have

been told to explain why her festival on

February 1st comes before Mary’s on February

2nd. However, the poem Brigit Be Bithmaith

already mentioned actually calls her the mother

of Jesus:-

“she, the branch

with blossoms,

the mother

of Jesus!”

and the 7th c St

Broccan’s Hymn to Brigit refers to her again in

this way -:

“Brigit, mother of

my high King,

Of the

kingdom of heaven best she was born,”

In this perhaps can be seen the influence of Brigit as a mother goddess of the Gaels, finding her way back into the Christian Life of the saint through the words of the poet. Back to top

Brigit in the Kitchen and Commanding Kings

In keeping with her motherly attributes as nurturer and provider for her people, the stories of the saint show her at homely tasks such as the provision of food and give us as a backdrop not only churches and the land, but also the kitchen. One poem in the Book of Lismore gives Brigit’s request for God to bless the kitchen:

'Mo

cule-se

cule Fiadat find,

cule robennach mo

Rí,

cule conni ind.’

Et dixit iterum:‘

'Ti Mac Mare mo

chara

do benna chad mo

chule!

fiaith in domain co

immel

ro[n] be immed la

sude.’

Et dixit tertio:

‘Ammo ruri-se

connic na hule-se

bennach a De, nuall

cen geiss,

dot laim deis in

enle-sa!'

My kitchen!A kitchen of fair God.

A kitchen which my King has blessed,

A kitchen with somewhat therein.

And she said again:

May Mary’s son, my Friend, come

To bless my kitchen!

The Prince of the world to the border,

May we have abundance by Him!

And she said a third time:

O my PrinceWho canst do all these things!

Bless, O God - a cry unforbidden,

With Thy right hand this kitchen.

We see again in the life of the saint associations with the figure of Brigit as a Celtic goddess of the land, able to grant kingship. Even though this emphasis may have been a cynical and political invention to gain power for the sept, it made sure that echoes of the goddess endured. In one story, Brigit goes to Aillil, the King of Leinster to ask for the sword of Dubthach, her father, and the freedom of a slave. In return she promises him excellent children, the kingship for his sons and heaven for himself. He is not satisfied with that, and asks instead for length of life in his realm and victory in his conflict with the northern half of Ireland. This Brigit grants. When she wants stakes and wattles to build her house at Kildare she sends her maidens to ask Aillil for them. On his refusal she strikes down his horses, takes the stakes and does not release the horses until Aillil agrees to give her a hundred horseloads to build her house. He also fed the builders who built her great house and paid them their wages. In return, Brigit left as a blessing that the kingship of Leinster should be till doomsday from Aillil.

This last story is interesting because it typifies Brigit as a strong character who does not tolerate not getting her own way even when dealing with the high king. Her actions are of a goddess dealing with lesser mortals, confident in her superior powers and then generous with her supernatural gifts when she has what she wants. It contradicts what the author of the Life in the Book of Lismore says about her later on:

“Now there has never been anyone more bashful or more modest, or more gentle, or more humble, or sager or more harmonious than Brigit. She never washed her hands or her feet or her head among men. She never looked at the face of a man. She never would speak without blushing...”

There are other female saints who command because they assume the authority of God, but it is tempting here to see the Christian idea of the perfect woman overlaying the pre-Christian figure of the powerful goddess. Back to top

Although some of the stories, like that of her encounters with Ailill, depict her as a goddess-like figure able to grant victory in battle there are others where a different ethos seems to be at work, one in which the avoidance of conflict and war are seen as virtues. Possibly this reflects a moving away from the earlier values of a warrior society into the Christian era. She often appears as a mediator and in one story in the Liber Hymnorum, when two brothers in conflict ask her for her help in battle, she puts a film over their eyes so that they are unable to recognise eachother and thus conflict is avoided. In this depiction she is on the side of peace and promises her protection, not in battle this time, but if weapons of war are abandoned. The 8th century Bretha Crólige (19) (a collection of legal material relating to medical provision) gives a list of 12 women whom the rule of nursing in Irish law excludes (they are instead compensated by a fee being paid to their kin). One category is 'a woman who turns back the streams of war' and a gloss on this states 'such as the abbess of Kildare or the female aí bell teoir, one who turns back the manifold sins of war through her prayers.' Whether or not this duty was ordained in Brigit's time we cannot know, but it was obviously one of the functions of the abbess of Kildare during the years when the sacred flame was tended there. Back to top

Brigit's function as a goddess of healing is also documented in the Lives. The blood from a gash on her head heals two dumb women, she brings a stillborn baby back to life by breathing on him. In one rather controversial story in the early life by Cogitosus she helps a young nun who has become pregnant by restoring her to her former state. She restores lepers to health - in one story she sends a leper to bring her some rushes and from the place where he has taken them a well appears; he bathes his face in the water and is cured. There are several connections of Brigit with water and healing, not only in the holy wells as we have seen but also the river she falls into which is stained red with her blood has the power to heal. The water she has bathed in has a similar healing power . It is not uncommon for the Celtic saints to be associated with healing wells (wells are also liminal places where the water appears out of the earth) but unique to Brigit, and reminiscent of Brigit the goddess, is that she had a magical girdle which could heal, and this she gave to a poor woman who came to beg from her so that thereafter the woman was able to make her living from it. This girdle reappears in the folklore connected with Saint Brigit. The Crios Bríde was woven from straw at Imbolc and men and women would step through it three times, kissing it and stepping through it right foot first, as a symbolic act of rebirth in order to ensure health and protection for the year ahead. While doing so they recited the following:

Crios, Crios Bríde

mo chrios,

Crios na gceithre

gcros;

Muire a chuaigh

ann,

Agus Bríd a tháinig

as;

Más fearr sibh

inniu,

Go mba seacht fearr

a bheas sibh

Bliain ó inniu.

The Girdle, the girdle

of Brigit, my Girdle,

The girdle of the four crosses,

Mary entered it,Brigit emerged from it;

If you be improved today,

May you be seven times better

A year from today.

(20)

Back to

top

Brigit Associated with the Number 8

Brigit is associated with the number eight in her life in the Book of Lismore. The author emphasises that “On the eighth of the month Brigit was born, on a Thursday especially: on the eighteenth she took the veil: in the eighty-eighth (year of her age) she went to heaven. With eight virgins was Brigit consecrated, according to the number of the eight beatitudes of the Gospel which she fulfilled, and it was the beatitude of mercy that Brigit chose.” Exactly what the significance of the number eight was is hard to say. It may have been simply that it was the number of the beatitude of mercy. Eight is not normally a particularly significant number in Celtic religion. We do find it, however, in the Eight Parts of Man, medieval texts found in Irish and Welsh, which assert that man is made from the elements of the sun, the sea, stone, earth, clouds, wind, the Holy Spirit and Christ, thus signifying human wholeness. It was the eight sons of Míl who invaded Ireland and the ancient Irish and Welsh board games are thought to have had eight opposing pieces on either side. These again convey a sense of eight being a complete and forceful number. Rees and Rees point out that eighteen seems to be a completion of seventeen (a significant number itself, connected with times of transition and division of land) and note that Fergus uprooted the forked tree at his eighteenth attempt and that Maeldúin himself made up eighteen on his Voyage.

In Europe of the Middle Ages eight is given as the number of return, soul and body, or reincarnation and we might note that the ability to return seems to be an attribute of Brigit. In our time numerology assigns eight as the number of completion. It is sometimes said to represent the two spheres, heaven and earth, joined and touching, which is reminiscent of the flame seen to come from the house where the child Brigit was sleeping, which joined heaven and earth - an illustration of the liminal imagery connected with Brigit. Back to top

In fact there are many associations of Brigit with liminality, with being on the threshold between two places or times. This was a powerful concept in the Celtic imagination since the places and times between the worlds are full of potential, of magic, of power - they are not limited or restricted since they are neither one thing nor the other but are connected to dynamic states of transition. The keywords connected with liminality are, in fact, transition, interconnection, power and dynamism. We might consider nuclear physics when thinking about liminality. Subatomic particles have a dual nature - they may be particles or waves; they exist in a state of dynamic potential, of probability, not certainty. Moreover, to quote Fritjof Capra, “Quantum theory has shown that subatomic particles are not isolated grains of matter but are probability patterns, interconnections in an inseparable cosmic web that includes the human observer and her consciousness.” And again - the properties of matter’s basic patterns, the subatomic particles, “can be understood only in a dynamic context, in terms of movement, interaction and transformation.”(21) We could say, therefore, that in liminal times and states matter is fluid and its shape and form may be influenced by those who observe them.

Liminality occurs as I have said, where two times or places or things meet, such as sunset and sunrise, the turn of the seasons, the turn of the century, the millennium. Liminal places are the shore which is neither land nor sea, boats which are neither land nor sea, bridges which are neither one place nor the other - or of course the threshold, which is neither in the house nor outside the house. Stories, an important part of Celtic oral culture, may cast a liminal spell since the characters, events and places in them exist and yet do not exist. Adolescence and the menopause are liminal states, times of transition when one is neither child nor adult, neither mother nor crone. In these states, at these times, in these places one is powerful, unstable and therefore fluid, sensitive to the call of the Otherworld. At Samhain, the meeting of autumn and winter, the veil between the worlds is thin and the dead step through. So at Brigit’s festival of Imbolc, the meeting place of winter and spring, the veil is thin and perhaps the spirits of those yet to be born step through, as the seeds start to germinate in the still hard earth.

Brigit is born at sunrise as her mother is stepping onto the threshold carrying a bucket of milk and she is bathed in the milk. She is an intermediary between the king and someone he is about to punish with death in two of the stories. Being unable to eat the druid’s food, she is fed on the milk of a red-eared cow - in other words, an Otherworldly cow. She is the child of a king and a slavewoman; her stepfather is a druid but she becomes Christian. And thus she is between the world of the two religions and becomes a powerful link between them. Back to top

![]()

![]()